discography

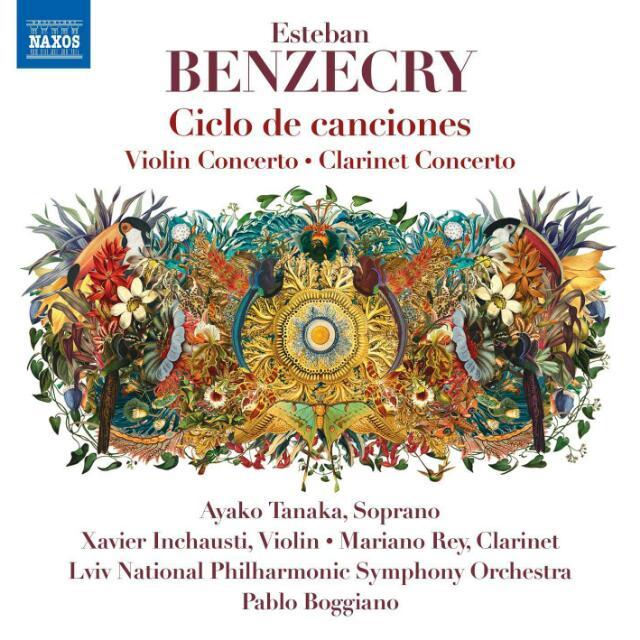

Ciclo de canciones – violin Concerto – Clarinet Concerto by Esteban Benzecry

Tracks

BENZECRY, E.: Ciclo de canciones / Violin Concerto / Clarinet Concerto (Ayako Tanaka, Inchausti, Rey, Lviv National Philharmonic, Boggiano)

French-Argentinian composer Esteban Benzecry has built up a distinctive body of work, from symphonies to works for solo piano. He stands as a worthy successor to such masters as Ginastera, Villa-Lobos and Chávez, with music that is suffused with ‘imaginary folklore’, flashes of colour, fieriness and reverie. The autobiographical Violin Concerto draws on South American folk motifs and rhythms, whereas in Ciclo de canciones he explores the meeting of two cultures, Argentinian and Japanese. The breathtaking dialogues between soloist and orchestra in the Clarinet Concerto recall Andean and pre-Hispanic times.

Benzecry, Esteban

Violin Concerto

1. I. Évocation d'un rêve (Evocation of a Dream) 00:11:02

2. II. Évocation d'un tango (Evocation of a Tango) 00:05:48

3. III. Évocation d'un monde perdu (Evocation of a Lost World) 00:10:21

Benzecry, Esteban

Traditional / Valderrama, Abdón Yaranga / Storni, Alfonsina / Berçaitz, Ana Lía / Caputi, Fernanda / Mistral, Gabriela, lyricist(s)

Ciclo de canciones (Song Cycle) (version for voice and orchestra)

4. No. 1. Del encuentro al camino (Together on the Path) 00:04:14

5. No. 2. Paz (Peace) 00:04:58

6. No. 3. Quiero ser (I Want to Be) 00:03:38

7. No. 4. La Noche (Night) 00:03:43

8. No. 5. Altar de la existencia (Altar of Existence) 00:03:49

Benzecry, Esteban

Clarinet Concerto

9. I. Ecos del Horizonte (Echoes of the Horizon) 00:08:10

10. II. Danzas Volcánicas (Volcanic Dances) 00:04:29

11. III. Baguala Enigmática (Enigmatic Baguala) 00:04:26

12. IV. Toccata Caribeña (Caribbean Toccata) 00:07:54

Total Playing Time: 01:12:32

Performer

A detailed track list can be found inside the booklet. The Spanish sung texts and English translations

are included in the booklet and may also be accessed at www.naxos.com/libretti/574128.htm

Recorded: 25–28 May 2019 at Lviv National Philharmonic Hall, Lviv Oblast, Ukraine

Executive producer: Pablo Boggiano • Producer and editor: Andrij Mokrytsky

Engineers: Andrij Mokrytsky, Oleksiy Grytzyshyn • Booklet notes: Benoît Duteurtre

Publisher: Esteban Benzecry • Cover design by Pablo Lembo

Year

2020

Record label

NAXOS

Duration

01:12:32

Comments

About this Recording 8.574128 - BENZECRY, E.: Ciclo de canciones / Violin Concerto / Clarinet Concerto (Ayako Tanaka, Inchausti, Rey, Lviv National Philharmonic, Boggiano) English French Esteban Benzecry (b. 1970) Violin Concerto • Ciclo de canciones • Clarinet Concerto Esteban Benzecry’s ‘imaginary folklore’ Throughout the course of the 20th century, an ever greater number of artistic exchanges took place between Europe and the young nations of Latin America, which were starting to add their achievements to the history of classical music. As European composers were setting off to explore the paths of the avant-garde, their Latin American counterparts were injecting music with a vitality that sprang from folk song and dance. The early heroes of a saga still unfolding today were the Argentinian Alberto Ginastera, Brazilian Heitor Villa-Lobos, and Mexicans Carlos Chávez and Silvestre Revueltas, along with other, lesser-known figures. French-Argentinian composer Esteban Benzecry is now proving himself a worthy successor to these masters, using his breathtaking talent to create vast musical landscapes inspired by his roots, his travels, his imagination and experimentation, and by a passion for and mastery of orchestral writing, as captured on this recording. As early as the 1920s, the Provençal composer Darius Milhaud, returning from Brazil full of that country’s songs and rhythms (including the song that gave its name to the very Parisian Le Boeuf sur le toit), had dreamed of a ‘Mediterranean music’. This would not be restricted to works from the Mediterranean basin, but would embrace all music with a ‘Latin’ essence, linking countries on both sides of the Atlantic in a single dreamlike and colourful ideal. With that same ideal in mind, many South American composers travelled to Paris to complete their training—among others, Villa-Lobos studied with Fauré, and Piazzolla with Nadia Boulanger (who encouraged him to find his own path, drawing inspiration from his Argentinian roots). Similarly, Esteban Benzecry, who was born into a family of musicians in Lisbon (in 1970) but grew up in Buenos Aires—where his introduction to music came via the guitar—left Argentina for France in 1997 to study at the Paris Conservatoire. The Paris of the late 20th century was very different from that of the années folles, when folk music was very highly regarded. A new avant-garde was setting the tone, a trend focused on radical experimentation and research. Displaying a wonderful independence of spirit, however, Benzecry continued to plough his own furrow while enriching his idiom with the processes, ideas and colours of spectralism and electroacoustic music, and acknowledging the master composers whose works most closely matched his own aspirations: figures such as Messiaen and Dutilleux, and, more generally, the French symphonic music which, in the wake of Debussy and Ravel, had turned the orchestra into a magical instrument. I first met Benzecry in 1999, when I was head of the Musique Nouvelle en Liberté association (which later commissioned the final version of his Violin Concerto), and I still remember the impression his originality made on me. Untroubled by the various aesthetic splits and disputes of the Parisian music scene, still pretty virulent even then, Esteban Benzecry was simply himself, his music as natural as his accent; brick by brick, he built up an instantly recognisable body of work. This is why even those who might have expected to feel no immediate connection with him have been quick to recognise the authenticity of his voice, and why he soon earned the support of, in particular, the Orchestre Pasdeloup, and then of the Radio France ensembles as well. Over the years, he has gone on to win similar endorsement around the world too, in Europe and both North and South America, as can be seen from the list of prestigious orchestras that have programmed his music, including the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic and the Simón Bolívar and Gothenburg Symphony Orchestras. Benzecry has also achieved something all composers dream of: the commitment of individual performers who love his music and want to promote it. The eminent Venezuelan conductor Gustavo Dudamel, for example, has become a spokesman for his orchestral work Rituales Amerindios (which can induce trance-like states worthy of Stravinsky), but his works have also been performed by such leading soloists as cellist Gautier Capuçon, violinist Nemanja Radulović and clarinettist Valdemar Rodríguez, as well as the artists who appear on this recording: conductor Pablo Boggiano, violinist Xavier Inchausti, soprano Ayako Tanaka and clarinettist Mariano Rey. They all know that a love for instruments, an understanding of every individual instrument’s potential and how it is played, and an innate feel for the orchestra and its colours are the foundations of Benzecry’s imagination, as vibrantly abundant as the Baroque Latin American novels that the world discovered in the latter half of the 20th century. If I had to sum up Esteban Benzecry’s aesthetic, I’d call it music of travel, rather than of sentiment—or perhaps ‘pictorial’ music, which is the term used by the composer himself, who studied art before deciding to focus on a career in music and who sometimes calls himself a ‘scenographer of sound’. Breaking away from Romanticism and the exaggerated expression of the self (as Debussy did from Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune onwards), Benzecry invites us to travel with him into magical, sometimes disturbing worlds that we discover through melodic impulses, flashes of colour, tension, fieriness and reverie. Songs emerge within it like the sounds of the forest or Aztec rhythms that constitute his ‘imaginary folklore’. Folk dances can acquire an appealing simplicity before giving way to subtle explorations of harmony and timbre. The composer expresses his personality through this soundscape painter’s soul; and it’s by discovering his worlds that we discover the man himself. Violin Concerto (2006–08) The Violin Concerto came into the world in several stages. First came Évocation d’un rêve (‘Evocation of a Dream’), composed at the Casa de Velázquez, in Madrid, where Esteban Benzecry was composer in residence between 2004 and 2006, and premiered in 2006 in Paris by the Orchestre Pasdeloup and soloist Nemanja Radulović. Évocation d’un monde perdu (‘Evocation of a Lost World’), also began life as a stand-alone work, given its first performance in 2008 by the same artists. Encouraged by the success of these two pieces, Benzecry decided to incorporate them into a large-scale concerto, adding a central movement: Évocation d’un tango (‘Evocation of a Tango’). The Violin Concerto, in its definitive version, received its premiere on 5 December 2009 at the Salle Pleyel in Paris, with Radulović and the Orchestre Pasdeloup conducted by Wolfgang Doerner. The Concerto is dedicated to Nemanja Radulović, Benoît Duteurtre and the Orchestre Pasdeloup. The composer himself has qualified this vast score as ‘autobiographical’ in nature. At times its character becomes elegiac, lyrical, deeply expressive, driven by the violin writing. Benzecry makes full use of the instrument’s potential and the language of virtuosity as he presents the three evocations, in which various folk-based sources are discernible. As he notes, in the first movement there are ‘brief motifs that evoke Spanish music, cante jondo and the music of tablaos [flamenco venues], but set in the context of a contemporary orchestration. I’m also evoking my Sephardic ancestry. As a whole, this is a kind of imaginary folklore which mingles with dreamlike forests inhabited by non-existent birds.’ As for the second movement, Évocation d’un tango: ‘Here I’m evoking one aspect of my Argentinian roots, the city of Buenos Aires, where I’ve spent much of my life. In the hazy atmosphere of the opening, rhythms and melodies intertwine among fragments of tango. In the central section, the violin plays an ardent melody, before revisiting the haziness of the beginning.’ Finally, in Évocation d’un monde perdu: ‘I develop melodies and rhythms rooted in South American folk music—the baguala, for example, or the carnavalito (a dance from northern Argentina) or malambo (a competitive dance for men only, its footwork inspired by the rhythm of galloping horses)—while also incorporating traces of a pre-Colombian world. The opening depicts man’s lament over his solitude, or protestations about his fate. Then I play with the lyrical possibilities of the violin, while the woodwind imitate the song of the soloist in the style of quenas (indigenous Andean flutes). The enchantment is shattered by the sudden interruption of a violent episode which then leads to a kind of toccata in which I explore the virtuosity of the violin in a moto perpetuo.’ Ciclo de canciones (‘Song Cycle’) (2014) Benzecry’s Song Cycle for coloratura soprano and orchestra similarly emerged in various stages. When he met Japanese soprano Ayako Tanaka, the composer was instantly captivated by her voice. The first song, Del encuentro al camino (‘Together on the Path’), was written for her in 2014 and sets a text by Benzecry’s wife, the artist and poet Fernanda Caputi. Its subject is the meeting of two cultures, with Argentina represented by its national flower—the scarlet flower of the ceibo, or cockspur coral tree—and Japan by the sakura, or cherry blossom. Having written this first piece, Benzecry was keen to start work on a longer cycle for voice and piano, again: ‘inspired by that exquisite, delicate voice, so full of variety and nuance. It led me to create lyrical, virtuosic music that makes the most of the uppermost register, from the subtle vocal writing of La noche to the untamed virtuosity of Altar de la existencia. Then, in a third and final phase, Ayako Tanaka and conductor Pablo Boggiano commissioned me to create an orchestral version of the cycle. This was premiered at the Centro Cultural Kirchner in Buenos Aires on 24 February 2017 by Argentina’s National Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Pablo Boggiano.’ It was recognised by the Argentinian Association of Music Critics, who awarded it their prize for best world premiere of 2017. It is dedicated to Ayako Tanaka and Pablo Boggiano. As well as the opening poem by Fernanda Caputi, the five-song cycle sets the following texts: Paz (‘Peace’) by the Argentinian poet Alfonsina Storni (1892–1938); Quiero ser (‘I want to be’), by her compatriot Ana Lía Berçaitz (b. 1947); La noche (‘Night’), by Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral (1889– 1957); and Altar de la existencia (‘Altar of Existence’), which is a translated excerpt from a Quechua text belonging to the Coracora community in Peru. Traditionally, men and women would have taken turns to sing its different verses, dealing with love, the origins of existence, and the sacred river to which they take their offerings. These five songs, which can either be sung as a cycle or individually, are linked by ‘the presence of nature, questions about existence, and Latin America, as seen from a feminine perspective and represented by a female voice’. Clarinet Concerto (2010) The Clarinet Concerto is a breathtaking dialogue between solo instrument and orchestra. It was written in 2010, on the initiative of clarinettist Valdemar Rodríguez, the Academia Latinoamericana de Clarinete, and the FESNOJIV (Venezuela’s National Network of Youth and Children’s Orchestras, also known as El Sistema). The premiere was given on 4 September 2016 at the Centro Cultural Kirchner in Buenos Aires by Valdemar Rodríguez and the Orquesta Sinfónica Juvenil Nacional José de San Martín, conducted by Pablo Boggiano. The score is dedicated to Valdemar Rodríguez and the Academia Latinoamericana de Clarinete. In the first of the Concerto’s four movements, Ecos del horizonte (‘Echoes of the Horizon’), Benzecry creates ‘an echo-like reverberation effect between the soloist and the orchestra, presenting us with a vast space of solitude and introspection’. Next comes Danzas volcánicas (‘Volcanic Dances’), ‘a tribute to the many volcanoes of the Americas’. In this dance, which is underpinned by the rhythms of earthquakes and eruptions, we find ‘imagined folk themes, pentatonic scales that recall Andean folk music, a carnavalito rhythm, multiphonic sounds and a dialogue between the soloist and the percussion, which dance to an irregular rhythm’. The third movement, Baguala enigmática (‘Enigmatic Baguala’), makes reference to a folk genre of western Argentina, of pre-Hispanic origins, typical of the Salta Province, and performed by a single singer, the bagualero. ‘In this very lyrical movement,’ notes Esteban Benzecry, ‘the solo voice sings a made-up baguala while pizzicato strings imitate the strumming of the charango (a small guitar, traditionally made from an armadillo shell). By using a variety of multiphonic procedures and different types of attack and breathing, I wanted to recreate the sound of traditional flutes such as the quena or panpipes using conventional orchestral instruments.’ The work ends with the Toccata caribeña (‘Caribbean Toccata’), in which the composer’s aim was ‘to express the joy and the festive and sensual feel of Caribbean rhythms by evoking the style of the region’s folk music rather than quoting directly from it. This movement makes extremely complex rhythmical and virtuosic demands on both soloist and orchestra.’ Benoît Duteurtre Writer and producer at France Musique English translation: Susannah Howe

Related Works